Naula and Dhara

Traditional Water Harvesting in Uttarakhand – A Study of Naula & Dhara Systems

The Himalayan terrain faces unique hydrological challenges due to steep slopes, limestone geology and limited groundwater retention. To adapt to these conditions, indigenous communities in Uttarakhand developed intricate water management systems known as Naula and Dhara, which emerged as the backbone of agrarian life for centuries. Naulas are elaborately constructed step-well–like reservoirs lined with stone to collect subterranean water, while dharas are natural springs protected by stone structures to preserve their purity. Both systems reflect exceptional engineering knowledge combined with spiritual reverence for water. These structures are closely linked to the region’s socio-cultural fabric. Rituals such as dhara poojan, linked to marriage ceremonies, and other community gatherings reflect the sacred status of water in Himalayan life. Historical evidence and inscriptions indicate sustained patronage from royal dynasties, especially the Katyuri and Chand rulers, leading to the construction and maintenance of numerous naulas and dharas across Kumaon and Garhwal.

“Our ancestors built water systems that did not conquer nature – they collaborated with it. Naulas and dharas remind us that sustainability is not a modern invention but an ancient inheritance.” — Sarika Pant, Cultural Heritage Writer, Uttarakhandi.com

However, climate change, deforestation, unplanned development and declining community participation have jeopardised these ancient systems. Modern reliance on piped water supply has further reduced their significance among younger generations. Preserving this hydraulic heritage is essential not only for cultural continuity but also for revitalising sustainable, community-led water management models.

Traditional Hydraulic Wisdom

The Living Heritage of the Indian Himalayan Region

Spanning 12,000 square kilometres, the Himalayas are home to nearly 15,000 majestic glaciers. The towering slopes and limestone rocks of the central Himalayan region pose a significant challenge to perennial water storage. To sustain life in these harsh terrains, people relied completely on a network of springs and waterfalls that were curated, protected and revered as part of their everyday lives. Indigenous communities ingeniously crafted hydraulic water systems such as Naula and Dhara, showcasing a harmonious balance between sustainability and hydrology.

Dharas and naulas are traditional water management systems widespread in the central Himalayan region, especially in Uttarakhand and Nepal. They functioned as shared water sources — partially covered, community-protected and linked with divinity to ensure ecological sanctity. Agriculture has been the backbone of Uttarakhand’s economy since the medieval period. Dating back to the 7th century CE, these structures are believed to have been popularised during the rule of the Katyuri and Chand dynasties in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand.

Across countless villages in the Himalayan foothills, dhara and naula remain a vital lifeline even today. These springs are not only marvels of ancient knowledge and architecture but also symbols of innovative hill hydraulics. Dhara and naula embody a sacred entity in which water is more than a natural resource – it is a manifestation of the divine and carries sanctity in every drop. Built along slopes to collect water, they reflect the geomorphological wisdom of the Pahadi community. These structures are integral to community life and hold immense cultural, traditional and spiritual importance. Deeply woven into the cultural history of the Himalayas, naula and dhara combine hydro-engineering, theology and spirituality, offering the modern world valuable ecological insights.

Etymology

The word Dhara, or dhaar धार in Hindi, refers to an open flowing water channel or natural spring emerging from the roots of oak trees on hillsides. Dhara is commonly used in Hindi, Kumaoni and Garhwali, and is pronounced as dhaad धाड in the Jaunsar region — reflecting regional adaptation. Culturally, a dhara denotes a sacred water source worshipped as a manifestation of the holy river Ganga, believed to originate from Uttarakhand itself. Dhara is also considered a manifestation of the local patron deity who resides in water.

Similarly, the word Naula is derived from the Sanskrit term nauli/naula, meaning a stone-lined reservoir. Naula is articulated as nau नौ in Kumaoni. It refers to a carefully designed step-well–like water reservoir engineered to keep the water cool in summer and warm in winter. It collects groundwater that seeps naturally from the earth.

Origin, Cultural and Ecological Links of Dharas and Naulas

Oak forests play a critical role in sustaining natural water springs in the Himalayan hillsides. The dense canopy and water-retaining roots of oak trees maintain the perennial hydrological cycle of dharas and naulas. Subterranean water movement leads to the formation of a dhara, typically where percolated water emerges at the surface. The roots of the oak tree act like a sponge, fostering a high water-retention environment and providing a natural conduit for the outlet of the dhara. Oak trees are believed to be harbingers of rain and maintain soil biodiversity.

Dharas and naulas evolved alongside agricultural settlements in the Kumaon and Garhwal regions. With agriculture forming the economic and social foundation of the region since the medieval period, communities were compelled to preserve these spring-fed systems — which sustained livestock, farming and domestic life. Deeply embedded in local cultural practices, naulas and dharas determined the survival of the Pahadi community.

Historical Traces

Dharas and naulas originated many centuries ago and continued to be renewed and repaired under royal patronage or community stewardship. They are intrinsically linked with nature worship and reverence for water.

Archaeologically, dhara and naula date back to the early medieval period (8th to 12th century CE), although their origin is believed to be prehistoric. Archaeological evidence suggests that between the 7th and 11th centuries, the Katyuri kings patronised temples, stepwells and dharas as acts of gratitude and tribute to ancestors and nature.

The ancient naula of Syunrako village in Almora (declared a Monument of National Importance in January 2023), the naula of Katarmal Sun Temple, and the naula of Gangolihat are notable examples. These structures resemble temple architecture characterised by stone corbelling, sanctum-oriented designs and serpent iconography. Inscriptions of the Chand dynasty (11th to 18th century) mention grants of labour and land for the maintenance of naulas and dharas.

Architectural Grandeur of Naulas and Dharas

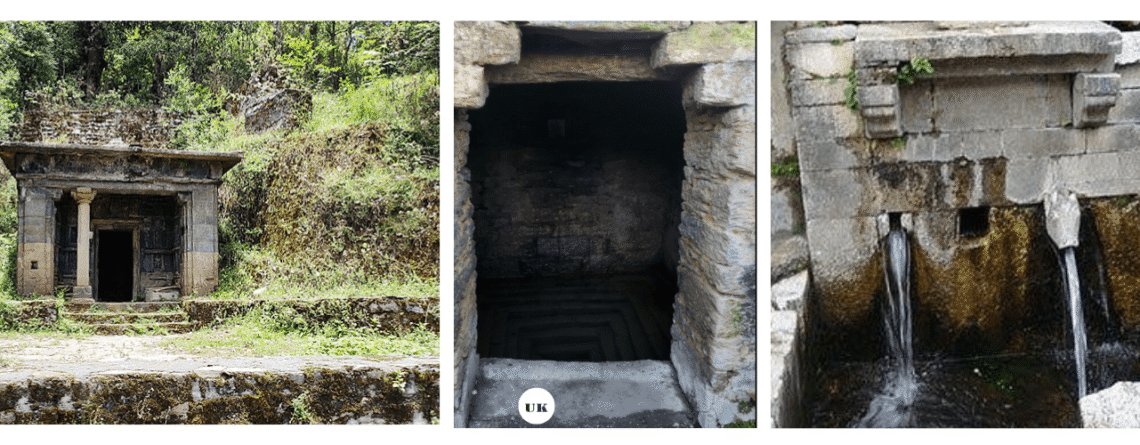

Naulas were precisely engineered to store groundwater seepage. Their outer appearance resembles a miniature stone temple with four pillars and a short entrance gate often adorned with carvings of Lord Ganesha and serpents. A naula is a stone-lined chamber dug deep into a seepage zone. Its floor is porous, made of broken stones to enable water collection. The roof is built with stone and mud, and the pillars are lined with dressed stones to prevent dust, evaporation and contamination.

Typically, naulas have three to five descending steps allowing individuals to enter the chamber for water testing, ritual cleaning and maintenance. Water is traditionally collected in the early morning considered an auspicious start to the day. Rituals such as post-wedding ceremonies or naming ceremonies are intimately connected with naulas, reinforcing environmental stewardship and the sacredness of water.

Key architectural features of naulas:

- Constructed using natural dry materials, primarily carefully stacked stones

- Underground chamber is pyramid-shaped for water storage

- Steps built on multiple sides of the naula and covered by a pyramid-like temple roof

- Drainage outlets manage overflow and prevent contamination

- Religious motifs carved on pillars emphasize sacred importance

In contrast, dharas are natural springs originating from the roots of oak trees, protected by stone structures to prevent contamination. Unlike naulas, dharas do not involve elaborate architecture. They serve as open-access drinking water sources focused on spring preservation rather than storage.

Traditionally, dharas are believed to possess divine origin. Local legends link them to the patron goddesses Nanda Devi and Dhari Devi, protectors of the region. Oral histories dating back nearly 600 years recount the dhara-poojan tradition associated with the ancient temple of Goddess Dhari Devi in the river Alaknanda.

Dharas play a central role in community gatherings, religious festivities and marriage ceremonies. Newly-wed brides traditionally visit the village naula or dhara before beginning their marital life symbolising the ancestral bond between community and nature.

Construction skills for naulas and dharas are rooted in generational knowledge and community responsibility, passed down through families and social groups.

Dhara Poojan

Dhara poojan is a post-wedding ritual deeply rooted in Vedic and Himalayan customs that regard water as a manifestation of the divine. The earliest references appear in the Rig Veda. The 129th hymn, Nasadiya Sukta, from the 10th Mandala states:

“There was no existence or non-existence,

neither matter nor space,

no atmosphere, no sky, nor realm beyond.What covered it? What protected it?

And in whose keeping was the cosmic water deep and unfathomable?”

The Rig Veda attributes divinity to water. Thus, dhara poojan is a continuation of ancient ecological reverence and cultural identity. In this ritual, the newly-wed bride venerates the dhara, expressing gratitude to nature and seeking blessings for prosperity in her new household. It marks the bride’s integration into her marital family and reinforces the cultural obligation to honour and conserve natural resources.

The bride dresses in traditional attire with jewellery and is accompanied by her in-laws and village women singing sakun-akhar folk songs. At the dhara, the priest chants Sanskrit mantras and offers prayers to water and local deities. The bride collects water in a copper gagri and carries it home on her head. The water is offered to family members, who bless her and give token gifts. Dhara poojan is not merely a cultural ritual – it is a practice deeply rooted in environmental consciousness.

Declining Dharas and Naulas

Several factors contribute to the alarming decline of naulas and dharas today:

- Climate change, which exacerbates seasonal drying of springs

- Unplanned and rapid infrastructure development disturbing recharge zones

- Deforestation leading to reduced soil moisture and spring yields

- Natural disasters such as landslides, avalanches and earthquakes destroying ancient structures

With the decline of dharas and naulas, communities now face water scarcity and must compromise on water quality. The degradation of springs threatens cultural traditions and prompts migration away from ancestral lands, impacting tribal and native populations.

Modernization has reduced community involvement in maintaining traditional water sources. Heavy reliance on piped water supply has led many – especially the younger generation to neglect naulas and dharas. Migration for education and employment has further weakened intergenerational transfer of traditional ecological knowledge.

Although these water structures remain deeply meaningful to the older generation, their cultural relevance is rapidly fading among the younger population. It is crucial to protect this ancestral legacy that intertwines spirituality, ecology and community identity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a Naula in Uttarakhand?

A Naula is a traditional Himalayan water reservoir built to store naturally seeping spring water. Found mainly in Kumaon and Garhwal regions of Uttarakhand, naulas are designed as miniature temple-like structures with an underground chamber lined with dressed stones. The porous stone floor allows groundwater seepage to collect naturally, keeping it cool in summer and warm in winter. Naulas represent one of the oldest decentralized water management systems in India and have been a reliable source of clean drinking water for centuries.

What is a Dhara in Uttarakhand?

A Dhara is a natural mountain spring where water flows openly from the hillside, often emerging from the roots of oak trees (Quercus species). Protected through a simple stone structure to avoid contamination, dharas serve as continuous free-flowing drinking water sources for rural Himalayan communities. Dharas are deeply connected with religious beliefs and are often viewed as manifestations of Ganga, Nanda Devi or Dhari Devi, reinforcing the sacredness of water.

How does a Naula work as a sustainable water system?

A naula functions by allowing groundwater seepage to accumulate inside a stone-lined chamber. The cool, shaded architecture prevents evaporation and biological contamination, acting as a natural filtration and groundwater recharge unit without electricity or chemicals. The design shows a deep understanding of hydrology, thermal regulation and aquifer behavior, proving the engineering brilliance of ancient Himalayan communities.

How does a Dhara function in the Himalayan landscape?

A dhara works by channeling natural spring discharge directly to the surface. As water percolates through soil and oak roots, it is naturally filtered and flows steadily through a spout or stone outlet. Because water is fresh, oxygen-rich and continuously replenished, dharas support drinking needs, livestock and agriculture without mechanical pumping or storage.

Which forests recharge Naulas and Dharas?

Oak forests are the lifeline of Himalayan springs. Oak roots retain rainwater like a sponge and release it slowly underground, feeding naulas and dharas throughout the year. Villages with dense oak forests show higher and more stable water flow, whereas areas with pine replacement and deforestation show drying springs, soil erosion and reduced water availability.

What is the religious and cultural importance of Naulas?

Naulas are not just water reservoirs—they are sacred water temples. Many naulas have carvings of Ganesha, serpents and local deities symbolising protection of water. Ritual practices, naming ceremonies and first-water offerings are performed at naulas to express gratitude to nature. Their sacred status encourages community ownership, cleanliness and environmental responsibility.

What is the cultural significance of Dharas?

Dharas play a key role in Himalayan social life, especially through the tradition of Dhara Poojan, in which newlywed brides collect holy water from the village dhara before entering their marital home. This ritual reinforces the bond between community, nature and sustainability, while reminding society to protect water sources for future generations.

Are Naulas still used in Uttarakhand today?

Yes. Many villages across Almora, Pithoragarh, Bageshwar, Nainital, Pauri and Rudraprayag still depend on naulas for drinking water. However, several naulas have become inactive due to spring depletion, migration and reduced community upkeep, highlighting the need for restoration and awareness.

Are Dharas still relevant today?

Dharas continue to serve as vital natural springs in many mountain settlements. However, their sustainability depends on forest conservation, soil stability and land-use planning. In villages where oak forests are preserved, dharas remain strong; where forests are degraded, dharas often dry up seasonally.

Why are Naulas declining today?

Naulas face threats from climate change, reduced spring recharge, soil erosion, road construction, concrete development, and cultural neglect. Without regular cleaning and repair, naulas fill with debris, making water inaccessible and unusable.

Why are Dharas disappearing across the Himalayas?

Dharas are drying up due to loss of oak forests, slope destabilisation, urban expansion, groundwater extraction and disruption of natural aquifers. Landslides and extreme weather events also damage the stone structures protecting dharas.

Why are Naulas important for sustainable water management?

Naulas are zero-energy, climate-resilient and community-driven water systems. Their revival can strengthen local water self-reliance, reduce pressure on piped supply networks and preserve Himalayan ecological heritage. They are a model for sustainable, nature-based water solutions.

Why are Dharas important for future water security?

Dharas provide continuous, naturally filtered drinking water and reinforce cultural bonds with nature. Protecting dharas supports water conservation, rural livelihood stability, ecological balance and heritage tourism, making them valuable for both community wellbeing and climate-adaptation planning.

Naulas and dharas stand today as living reminders of the Himalayan community’s profound understanding of nature, water and sustainability. These traditional water systems engineered centuries before modern hydrology emerged — demonstrate how indigenous knowledge can nurture life even in ecologically fragile mountain landscapes. Far more than infrastructure, naulas and dharas represent a cultural philosophy in which water is sacred, community is responsible and conservation is collective.

Yet their future is increasingly uncertain. Climate change, deforestation, unplanned construction, changing lifestyles and declining community participation are causing spring-fed systems to dry and heritage structures to collapse. With every abandoned naula or diminished dhara, the Himalayas lose not just a water source, but a legacy of identity, spirituality and ancestral science.

“When a naula dries or a dhara disappears, it is not only water that we lose – we lose memory, heritage and our connection to the mountains. Protecting these water systems is protecting who we are.” — Sarika Pant, Cultural Heritage Writer, Uttarakhandi.com

Reviving these water structures is not only about restoring old architecture – it is about restoring our relationship with the environment. Protecting oak forests, safeguarding recharge zones, documenting traditional knowledge and involving youth and local communities can ensure that naulas and dharas continue to serve future generations. Valuing these heritage water systems is essential to embrace sustainable, low-cost, nature-based solutions in an era of global water scarcity. The story of naulas and dharas is, ultimately, a story of harmony between land and people, resource and responsibility, past and future.